FIELDWORK IN SOUTH KOREA (SUMMER 2023)

AN IRB FOR THIS PROJECT WAS APPROVED, INCLUDING THE UTILIZATION OF AUDIO, PHOTO, AND VIDEO IMAGES. ALL NAMES AND LOCATIONS ARE PSEUDONYMIZED.

My summer fieldwork objective was to explore the relationship between Korean Buddhism and its temple cuisine as developed by nuns who have brought Korean Buddhist temple food (KBTF) across cultures to a global audience. Through participant observations and interviews, my research project identified how KBTF has been handed down by an oral tradition over 1600 years and how it has been modified to meet contemporary demands from modernization and globalization. A major objective was to learn about the principles of sustainability practiced by Buddhist nuns, including use of seasonal vegetables, fermented food, and overall vegetarianism.

Fermented sauces in earthen jars at Se Wun Sa Temple

After visiting several Buddhist nunneries and interviewing nuns this summer, I realized that rapid changes in Korean society make even decade-old scholarly work outdated. Therefore, attaining first-hand experience was essential to learn about current practices. There were five main areas of project-related activities that I was involved in this summer: 1) visiting individual nuns who are renowned for their knowledge and teachings of KBTF; 2) staying at a communal nunnery for one week; 3) visiting institutions specialize in teaching KBTF; 4) visiting the libraries known for Buddhist studies 5) attending the 18th Sakyadhita International Conferences on Buddhist Women.

The Venerable Ja Shim at her temple

The day after I arrived in Korea, in late May, I visited the Venerable Ja Shim to attend a celebration of Buddha’s birthday. Since being featured in Netflix’s Chef’s Table, Ja Shim’s temple has attracted international audiences. Ja Shim offers temple food programs on Sundays with cooking demonstrations and a dharma talk. I was able to attend two of those programs, learning about Ja Shim’s philosophy on nature and food. Participants are offered a meal and tea ceremony. In mid-June, the Society of Buddhist Solidarity for Ecology organized an event to raise environmental awareness and Ja Shim, with the help of assistants, prepared a meal for 400 people and gave a dharma talk. In August, during my third trip to Ja Shim’s temple, I had a chance to watch how she manages fermented sauces.

Lanterns lit in commemoration of Buddha’s birthday as part of a ceremony at Ja Shim’s Temple. Each lantern was paid by an individual, wishing wellness of family and ancestor.

The Venerable Ja Shim (right) during the Buddha’s birthday ceremony

The Venerable Ja Shim’s dishes prepared for the temple food program participants

The Venerable Ja Shim addresses attendees of an event, organized by the Society of Buddhist Solidarity for Ecology, focusing on environmental awareness and sustainability.

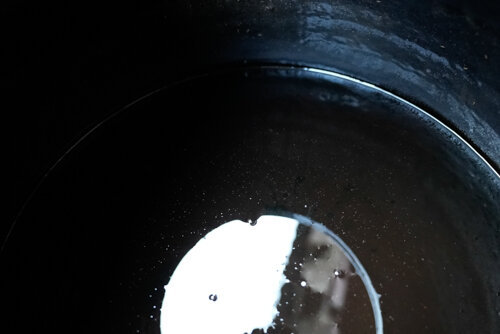

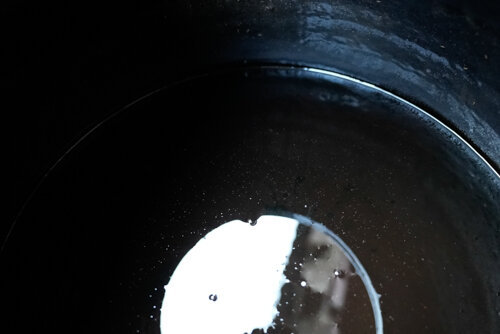

Fermented soy sauce in an earthen jar at Ja Shim’s temple

Ja Shim rearranging fermented sauces with her assistants

The Venerable Song Hyun was another nun with whom I conducted an interview at her temple in Dae Jeon, a two hour train ride from Seoul. Since 2021, Le Cordon Bleu in London campus has invited Song Hyun to teach KBTF as part of its Plant-based culinary program. At her temple, I was able to observe a special tea ceremony for her mentor nun, Beop Yeon.

A special meal (my plate) at Song Hyun’s temple

The Venerable Hae Ahn was another nun I met a few times this summer. I also participated in her kimchi-making seminar at the Korean Bhikṣuṇī Association. She overcame a serious illness, miraculously by changing her diet. While she was sick, kimchi broth was only thing she could eat. She has been teaching kimchi workshops ever since. She also saw how diet directly influences the behavior of young children during summer programs she organized. Hae Ahn acquired tremendous knowledge from two of her grandmothers who worked at the Royal Kitchen during the Joseon Dynasty (1492-1910) and her acupuncturist father. Hae Ahn’s knowledge about the medicinal properties of food proved to be valuable resource.

The Venerable Hae Ahn’s kimchi-making seminar at the Korean Bhikṣuṇī Association

A valley running through Young Ji Sa Temple

The one-week stay at Young Ji Sa was the highlight of my summer research, as I was given full access to observe everyday matters at the Buddhist nunnery. Young Ji Sa operates a four-year Buddhist institution for novice nuns—one of four remaining in Korea—and advanced studies in Buddhist precepts. Young Ji Sa is located deep in the mountains with running water from the valley. It is isolated in a sense that it requires one hour’s driving to go to a market. While I stayed there, there were twenty-four in-residence nuns, and a few additional nuns who were commuting to take courses on Buddhist precepts. All in-residence nuns were quite busy with Buddhist practices and communal works, in addition to their respective responsibility at the temple.

A view of Young Ji Sa Temple

A view of Young Ji Sa during the annual Lotus Sutra recitation

Lotus Sutra recitation continues into the night at Young Ji Sa Temple

The abbess of Young Ji Sa asked me to arrive on July 1st during which time an annual seven-day ritual with continuous recitation of a Buddhist sutra, Pŏphwakyung (Lotus Sutra), was taking place. Right after this ritual, there was another ceremony to pay homage to and appease deceased souls and I was able to watch nuns preparing food. I also observed baru gongyang—the epitome of KBTF—that is a daily meal ceremony conducted in complete silence with no waste of food. It was a rare chance, as there are only a handful of monasteries still practicing baru gongyang these days. I participated in kmchi-making sessions and a Taichi session. Young Ji Sa has included Taichi in its curriculum since 1997 and it has helped nuns to endure long hours of studies. I also followed around a nun in charge of organic farming and helped her with planting.

A ritual during the last day of the Lotus Sutra recitation ceremony

Burning of spirit tablets during the last day of the Lotus Sutra recitation ceremony

A traditional kitchen at Young Ji Sa Temple

Burning of wood to cook rice on a caldron during the Lotus Sutra recitation ceremony

A snack made from rice cooked on a caldron

A tea ceremony to commemorate predecessors at Young Ji Sa Temple

Baru (four nested bowls) at Young Ji Sa Temple

Two Buddhist nuns harvesting radishes at Young Ji Sa Temple

At the 18th Sakyadhita International Conferences on Buddhist Women, I learned about current issues and concerns of Buddhist women around the globe. The Korean Bhikṣuṇī Association organized the Conferences that accommodated about 3,000 guests. After the conferences, I participated in the post-conference trip to historic temples, which provided me opportunities to engage in conversations with nuns, scholars, and laypeople from around the globe. In early August, I was able to visit the Se Wun Sa temple—which hosted a welcome dinner for Sakyadhita International in June—to observe the Buddhist Festival of the Dead (paekchung).

The main Buddha Hall at Se Wun Sa Temple in Seoul

The last day ceremony at Se Wun Sa Temple for the Sakyadhita International

A welcome dinner (my plate) at Se Wun Sa Temple for the Sakyadhita International attendees

Korean traditional desserts at Se Wun Sa Temple for the Sakyadhita International attendees

The Buddhist Festival of the Dead at Se Wun Sa Temple

Oak tree with seeds of shiitake mushrooms at Se Wun Sa Temple

Kimchi-gwang (kimchi storage space) at Se Wun Sa Temple

(Fieldwork supported by the Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund in collaboration with the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University and the GSAS Matching Fund: Research for M.A. Final Thesis at Columbia University.)

AN IRB FOR THIS PROJECT WAS APPROVED, INCLUDING THE UTILIZATION OF AUDIO, PHOTO, AND VIDEO IMAGES. ALL NAMES AND LOCATIONS ARE PSEUDONYMIZED.

My summer fieldwork objective was to explore the relationship between Korean Buddhism and its temple cuisine as developed by nuns who have brought Korean Buddhist temple food (KBTF) across cultures to a global audience. Through participant observations and interviews, my research project identified how KBTF has been handed down by an oral tradition over 1600 years and how it has been modified to meet contemporary demands from modernization and globalization. A major objective was to learn about the principles of sustainability practiced by Buddhist nuns, including use of seasonal vegetables, fermented food, and overall vegetarianism.

Fermented sauces in earthen jars at Se Wun Sa Temple

After visiting several Buddhist nunneries and interviewing nuns this summer, I realized that rapid changes in Korean society make even decade-old scholarly work outdated. Therefore, attaining first-hand experience was essential to learn about current practices. There were five main areas of project-related activities that I was involved in this summer: 1) visiting individual nuns who are renowned for their knowledge and teachings of KBTF; 2) staying at a communal nunnery for one week; 3) visiting institutions specialize in teaching KBTF; 4) visiting the libraries known for Buddhist studies 5) attending the 18th Sakyadhita International Conferences on Buddhist Women.

The Venerable Ja Shim at her temple

The day after I arrived in Korea, in late May, I visited the Venerable Ja Shim to attend a celebration of Buddha’s birthday. Since being featured in Netflix’s Chef’s Table, Ja Shim’s temple has attracted international audiences. Ja Shim offers temple food programs on Sundays with cooking demonstrations and a dharma talk. I was able to attend two of those programs, learning about Ja Shim’s philosophy on nature and food. Participants are offered a meal and tea ceremony. In mid-June, the Society of Buddhist Solidarity for Ecology organized an event to raise environmental awareness and Ja Shim, with the help of assistants, prepared a meal for 400 people and gave a dharma talk. In August, during my third trip to Ja Shim’s temple, I had a chance to watch how she manages fermented sauces.

Lanterns lit in commemoration of Buddha’s birthday as part of a ceremony at Ja Shim’s Temple. Each lantern was paid by an individual, wishing wellness of family and ancestor.

The Venerable Ja Shim (right) during the Buddha’s birthday ceremony

The Venerable Ja Shim’s dishes prepared for the temple food program participants

The Venerable Ja Shim addresses attendees of an event, organized by the Society of Buddhist Solidarity for Ecology, focusing on environmental awareness and sustainability.

Fermented soy sauce in an earthen jar at Ja Shim’s temple

Ja Shim rearranging fermented sauces with her assistants

The Venerable Song Hyun was another nun with whom I conducted an interview at her temple in Dae Jeon, a two hour train ride from Seoul. Since 2021, Le Cordon Bleu in London campus has invited Song Hyun to teach KBTF as part of its Plant-based culinary program. At her temple, I was able to observe a special tea ceremony for her mentor nun, Beop Yeon.

A special meal (my plate) at Song Hyun’s temple

The Venerable Hae Ahn was another nun I met a few times this summer. I also participated in her kimchi-making seminar at the Korean Bhikṣuṇī Association. She overcame a serious illness, miraculously by changing her diet. While she was sick, kimchi broth was only thing she could eat. She has been teaching kimchi workshops ever since. She also saw how diet directly influences the behavior of young children during summer programs she organized. Hae Ahn acquired tremendous knowledge from two of her grandmothers who worked at the Royal Kitchen during the Joseon Dynasty (1492-1910) and her acupuncturist father. Hae Ahn’s knowledge about the medicinal properties of food proved to be valuable resource.

The Venerable Hae Ahn’s kimchi-making seminar at the Korean Bhikṣuṇī Association

A valley running through Young Ji Sa Temple

The one-week stay at Young Ji Sa was the highlight of my summer research, as I was given full access to observe everyday matters at the Buddhist nunnery. Young Ji Sa operates a four-year Buddhist institution for novice nuns—one of four remaining in Korea—and advanced studies in Buddhist precepts. Young Ji Sa is located deep in the mountains with running water from the valley. It is isolated in a sense that it requires one hour’s driving to go to a market. While I stayed there, there were twenty-four in-residence nuns, and a few additional nuns who were commuting to take courses on Buddhist precepts. All in-residence nuns were quite busy with Buddhist practices and communal works, in addition to their respective responsibility at the temple.

A view of Young Ji Sa Temple

A view of Young Ji Sa during the annual Lotus Sutra recitation

Lotus Sutra recitation continues into the night at Young Ji Sa Temple

The abbess of Young Ji Sa asked me to arrive on July 1st during which time an annual seven-day ritual with continuous recitation of a Buddhist sutra, Pŏphwakyung (Lotus Sutra), was taking place. Right after this ritual, there was another ceremony to pay homage to and appease deceased souls and I was able to watch nuns preparing food. I also observed baru gongyang—the epitome of KBTF—that is a daily meal ceremony conducted in complete silence with no waste of food. It was a rare chance, as there are only a handful of monasteries still practicing baru gongyang these days. I participated in kmchi-making sessions and a Taichi session. Young Ji Sa has included Taichi in its curriculum since 1997 and it has helped nuns to endure long hours of studies. I also followed around a nun in charge of organic farming and helped her with planting.

A ritual during the last day of the Lotus Sutra recitation ceremony

Burning of spirit tablets during the last day of the Lotus Sutra recitation ceremony

A traditional kitchen at Young Ji Sa Temple

Burning of wood to cook rice on a caldron during the Lotus Sutra recitation ceremony

A snack made from rice cooked on a caldron

A tea ceremony to commemorate predecessors at Young Ji Sa Temple

Baru (four nested bowls) at Young Ji Sa Temple

Two Buddhist nuns harvesting radishes at Young Ji Sa Temple

At the 18th Sakyadhita International Conferences on Buddhist Women, I learned about current issues and concerns of Buddhist women around the globe. The Korean Bhikṣuṇī Association organized the Conferences that accommodated about 3,000 guests. After the conferences, I participated in the post-conference trip to historic temples, which provided me opportunities to engage in conversations with nuns, scholars, and laypeople from around the globe. In early August, I was able to visit the Se Wun Sa temple—which hosted a welcome dinner for Sakyadhita International in June—to observe the Buddhist Festival of the Dead (paekchung).

The main Buddha Hall at Se Wun Sa Temple in Seoul

The last day ceremony at Se Wun Sa Temple for the Sakyadhita International

A welcome dinner (my plate) at Se Wun Sa Temple for the Sakyadhita International attendees

Korean traditional desserts at Se Wun Sa Temple for the Sakyadhita International attendees

The Buddhist Festival of the Dead at Se Wun Sa Temple

Oak tree with seeds of shiitake mushrooms at Se Wun Sa Temple

Kimchi-gwang (kimchi storage space) at Se Wun Sa Temple

(Fieldwork supported by the Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund in collaboration with the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University and the GSAS Matching Fund: Research for M.A. Final Thesis at Columbia University.)